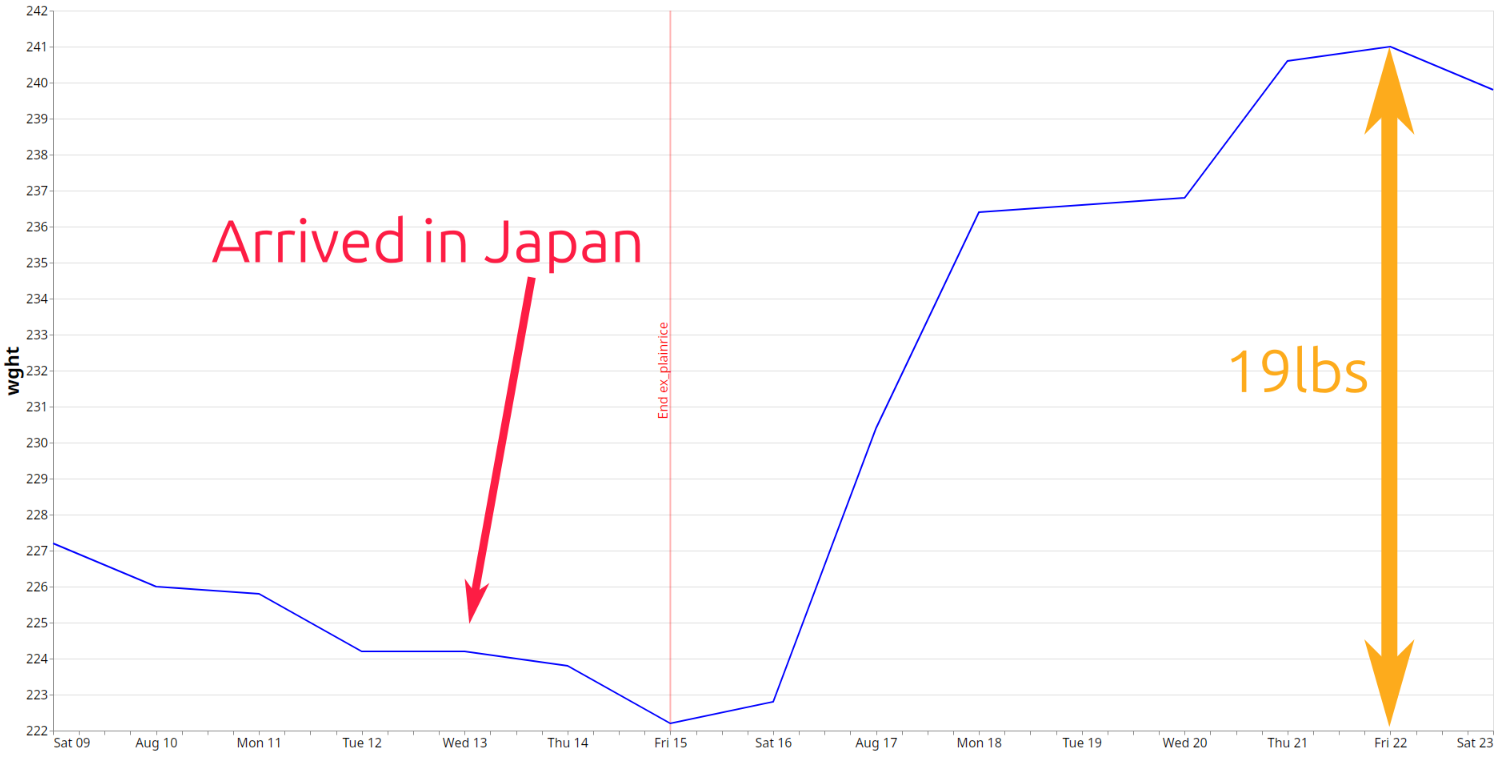

I went to Japan and gained 19lbs

Only partly clickbait. Lots of colorful graphs!

Oh, hey, I didn’t see you there. Remember a week ago when I proudly posted about losing 5.5lbs on a pure rice diet?

Since then, I’ve gained.. 19lbs.

I’ve gone from just over 222lbs to exactly 241lbs, much of it (14.5lbs) in the first 2 days. And it’s all to blame on…

Japanese Food!

That’s right. I’m currently vacationing in Japan. And the first 2 days here, I was still doing pure plain white rice.

But after that experiment ended, I thought I’d indulge in some local Japanese cuisine. I am, after all, on vacation.

Funnily enough, the foods that I craved most after 30 days of pure, plain, white rice were - sushi🍣 and onigiri🍙.

If you’re not familiar with onigiri, they’re very similar to sushi. They’re usually triangular shaped rice “balls” filled with e.g. salmon, sometimes vegetables, or other things. Wrapped around them, for ease of holding, is a sheet of nori seaweed.

So it’s essentially just a sushi sandwich.

This was somewhat funny to me because both sushi and onigiri are 80% rice. Why wasn’t I craving steak, or heavy cream, or something completely different? Who knows. But overall I think that’s another pretty decent sign for the rice diet.

In any case, these weren’t the only foods I ate. But for the first few days, they were the majority. I started branching out a bit more after that.

Yet despite going from a 100% rice diet to a maybe 75% rice diet, I gained nearly 15lbs in the first 2 days.

What gives?!

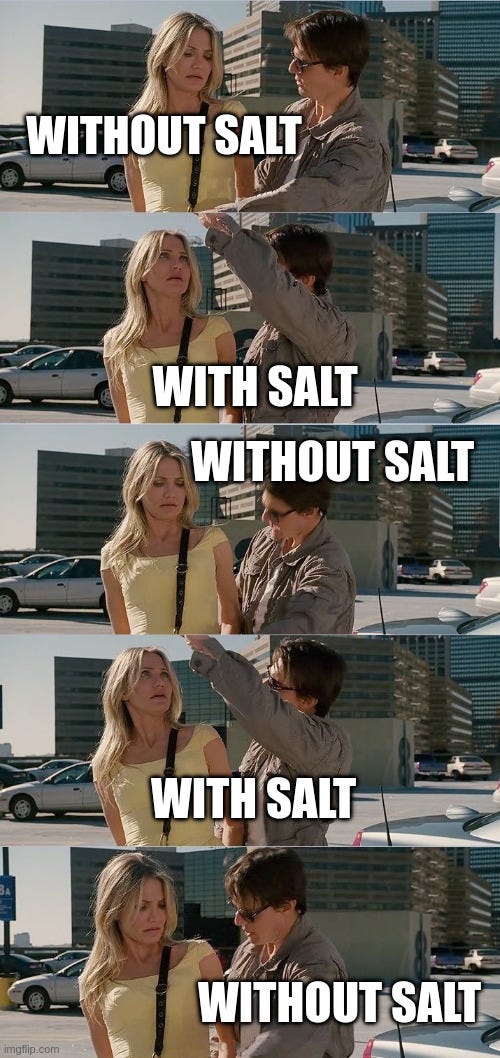

The answer is salt.

Diet Fragility

I think this was nearly all water retention, certainly the 15lbs in the first 2 days. I might’ve gained a few pounds of actual fat since then, but there’s no way you can gain 15lbs of fat in only 2 days.

I’ve previously written about water weight, so check that out if you haven’t seen it.

In short, there are several factors that influence the level of water your body retains, and sodium is one of the biggest levers. My normal heavy cream diet, ex150, is already pretty low in water retention. Almost everybody who goes on it quickly loses a few pounds of initial water weight, and regains those when going back to pretty much any other diet.

In a way, this makes ex150 somewhat “fragile” and this rice diet even more so. Now, fragility here isn’t necessarily bad. I just mean it in the sense that the diet is very low in water retention, and pretty much any deviation from it will produce a relatively large increase in water retention and therefore weight.

ex150 is very low-sodium

One factor that makes ex150 relatively low in water retention is that there is almost no added sodium. The only salt in the way I do it is whatever’s in the meat, and whatever’s in a few splashes of pasta sauce.

Now most pasta sauces do contain salt, but the amount I use on the diet is so low that I only get relatively little compared to most diets.

Whole Food’s fat-free marinara sauce, which is my favorite, contains 450mg sodium per 125mL (1/2 cup) serving. That’s more than I typically use, I tend to go for about 80g which should be roughly 80mL. So I’d get about 288mg of sodium a day, and whatever is in 150g of beef (~100mg). Heavy cream does have some sodium, although it’s not much - at the very extreme intake levels on a nearly pure heavy cream diet, it’s maybe another 250mg a day, for a total of about 600mg

That means I get less than 1/3rd the sodium limit for adult men via the RDA (2,300mg). Interestingly I couldn’t find an established minimum, but the American Heart Association seems to recommend at least 500mg, and they HATE salt.

I’m therefore getting just over the minimum amount of sodium even recommended by the AHA on my heavy cream diet.

This happened somewhat by accident; I stopped adding salt to my food a few years ago when experimenting with carnivore. Carnivore w/ added salt would give me crazy, persistent headaches, and I couldn’t pull it off for more than a few days until I cut out the salt completely.

I didn’t miss the salt at all, so when I stopped doing carnivore, I just didn’t add it back.

White rice is even lower in sodium

If you eat 3,000kcal of plain white rice, you’re getting less than 100mg of sodium per day, or 1/6th of the already low-sodium ex150 heavy cream diet. That’s probably about as low as you can go with real foods.

This also means that when you go on such a plain rice diet, some of the weight you’ll lose will be water weight. Still, I don’t think it’s a problem per se; after all I steadily kept losing weight. It wasn’t just one big plateau effect in the first week or so.

The issue is just the contrast: going from such an extreme low-sodium diet to one very high in salt.

Japanese food is super salty

I noticed this even on the last day of my rice diet, when I purchased some salted rice balls at a Japanese convenience store out of… convenience.

Not having had salted rice for 30 days, the salty taste seemed to nearly burn my mouth. It lingered on my taste buds and my entire mouth felt dried out, even after drinking some water, for an hour.

Japanese sushi rice is cooked with salt for flavor. How much? One random recipe I found says to use 1/2 tbsp of salt per 1 sushi roll or 1/2 cup of rice used. (Remember 1 sushi roll is cut into several slices, so it’s not just one piece.)

That is a TON of salt. Looking at the USDA database, 100g of sushi seems to range from 300-500mg of sodium. If you ate 3,000kcal/day of just sushi, you’d therefore end up with anything from 8,900mg of sodium to ~15,000mg of sodium a day.

That’s anywhere from 3.x to 6.5x the upper RDA limit, and compared to the rice diet’s 100mg it’s anywhere from 90x (!) to 150x (!!!1) the amount of sodium.

It is therefore not surprising (in retrospect) that I gained 19lbs in just a few days.

I went from pretty much the lowest-sodium diet imaginable (white rice) to an insanely high sodium intake (almost entirely sushi/onigiri). Salt leads to water retention. Water has mass. Mass increases weight.

Let me use this meme from the underrated 2010 rom-com Knight & Day to illustrate:

I obviously expected some water weight gain after going off the rice diet, but I wasn’t quite prepared for this. I’ve previously bragged about gaining 4.4lbs of “lean mass” in 24h, but I think I massively topped that this time.

I seem to have accidentally found both an even lower sodium diet (plain rice) and then vastly increased my water retention via accidental crazy salt intake. Water is “lean mass” so this would make a fun DEXA contrast. Or show you how little lean mass via DEXA really means if you don’t control for water retention.

Anyway. Fun was had.

Stuff I mostly ate

I quickly realized what was happening. And, maybe primed to think about salt due to the accidental “salted rice balls” experience, I wasn’t too panicked about my sudden extreme weight gain.

Having never been to Japan before, I had a small bucket list of foods I’d always wanted to try. Real Japanese sushi was just one thing on the list, although honestly, both sushi & onigiri are still some of my favorites. There is something about rice that just doesn’t get old!

Here’s an incomplete list of things I tried:

Sushi & Sashimi

Onigiri

Ramen

Tamagoyaki (folded square omelet)

Miso soup

Kobe beef

Thinly sliced roast beef

Soft boiled eggs cooked in broth

Natto (surprisingly unterrible! but it’s literally soybeans lol, so I only ate it once)

Mochi (a rice flour pastry), especially when filled with red bean paste

The legendary Shinkansen too hard ice cream, which is ice cream sold on the Shinkansen bullet train. Since the train doesn’t have refrigeration, they developed a special type of ice cream that is much colder and softens more slowly than regular ice cream. This means that, within the first 10 minutes of opening it, you cannot put a spoon into it at all as it is rock solid.

If you’re wondering, pretty much all of these check out exactly as people describe them and are definitely worth a taste. I was lucky to have a friend who’s lived in Japan for a long time, and both he and his wife had some great tips on what to try and where.

The coffee was generally outstanding no matter where I went, too.

Prices were slightly lower than in the U.S., but not dramatically. I’d say Japan is more expensive than most of Europe.

Overall, I’d say, Japan delivers. Whoever has been spreading memes about Japanese food & culture has been pretty spot-on.

Funny shaped cars. Driving on the wrong side of the road. Ridiculously low crime, to the point where people leave their wallets & phones in public places to indicate a table is taken. I think I’ve only seen 3 cops the entire time here.

Tiny convenience stores that sell everything under the sun. VERY high quality food next to deep-fried junk food. Lots of seafood. Extremely impressive bathtubs in extremely tiny hotel rooms.

Insanely punctual & fast trains. If you travel to Japan, PLEASE take the Shinkansen bullet train. It feels like you’re in a sci-fi movie, with tiny Japanese villages whipping by at 200mph just a few yards from your face. The first few minutes, looking out the window, I caught myself holding my breath.

Satiety gone within days

I’m sort of ashamed to say that, the longer I was off the diet, the more I veered into other, unhealthier cuisine including cookies, ice cream, and certain types of Japanese junk/fast food that weren’t just “rice, fish & salt.”

Curiously, I actually still got pretty decent satiety those first 2 days or so, despite gaining the insane amount of water. I remember overeating massively at least once, just because I wasn’t used to strong flavors on the rice diet. I was massively full and my stomach hurt, and I couldn’t eat for hours after that.

But within a day or 2, those same amounts of sushi & onigiri no longer gave me much satiety.

It’s a very weird feeling, because I had mentally anchored these foods in certain amounts giving me a certain feeling of satiety & fullness, and that just stopped happening. This has previously happened to me, coming off a bout of ex150.

There must be some lingering effect of such “metabolic fix” diets as ex150 or the rice diet: for 1-2 days, eating pretty much any normal food will still produce satiety.

But after eating those foods for just a few days, eating the exact same meals will trigger less and less satiety, until it’s quite literally zero.

It was fascinating to observe in myself. After enjoying both the flavor & still-present satiety from sushi and onigiri for the first day, I got confused as these feelings of satiety “slipped away” and I mentally tried to “hold onto them.” First I tried eating more of the same, but it simply made me more physically bloated without triggering the same satiety as before.

Then, I started branching out into other foods. I remember this from my pre-keto days when I was on the SAD and pretty much nothing would give me any satiety, ever. I’m talking eating 4,000kcal in one sitting and still wanting to eat more. The satiety switch wasn’t just off, it was gone.

That is what I felt myself sliding into this time with the Japanese food, despite starting out with the healthy & whole foods.

I think this gif of a raccoon trying to wash cotton candy illustrates the phenomenon well. I felt a certain metabolic state (satiety) just slip out of my hands, with no real clue where it had gone. Yesterday this made me feel satiated, what changed?!

Luckily, after a lifetime of metabolic dysfunction, I recognized this dynamic quickly, and I knew what to do: just go back on a metabolic fix diet.

But it is sort of messed up. I think my “veering off” the more healthy options like sushi and onigiri, and going more into the junky direction, is directly related to this “fading satiety.” Something that used to work stops working, and you just start thrashing and splashing in expanding circles, trying to hold on or find a replacement like a drowning man trying to hold onto something, anything. And at a certain point, you just go: “Fuck it. The healthy, whole foods aren’t giving me ANY satiety, might as well go for ice cream.”

I feel pretty lucky that I have since found not just one, but several diets that somehow fix my metabolism enough to provide a functioning satiety switch: my ex150 heavy cream diet, and, more recently, the rice diet.

What’s crazy once again is that I didn’t “ruin” my satiety switch by jumping straight into junk food. For the first few days, I actually only even craved whole, real foods that weren’t all that different from plain rice anyway.

But they completely ruined my satiety just the same. What was it about sushi and onigiri? The salt? The extra protein from the little bit of fish and egg? Some of the onigiri had mayo in it, although I tried to avoid those - could be the seed oils in the mayo?

Or was it “just” the excess variety & flavors? The fructose from the mochi I ate, even though I consciously started pretty slow on the sweet stuff?

How healthy is Japanese food?

It’s complicated.

One thing that fascinated me was that even if you lived entirely off the common little convenience stores like 7/11, you could actually make some really healthy choices, and many Japanese do.

All of the stores are loaded with sushi, onigiri, some fresh fruit, boiled eggs. There were also a lot of fast-food dishes that were probably not quite as “whole food” as rice + sliced fish, but relatively close. E.g. buckwheat noodles with soy sauce and vegetables, omelets, and so on.

So if you really want, and what I did the first few days, was picking those really clean & “whole food” choices even if they are technically “fast food.”

On the other hand, you can also buy some of the most “ultra-processed” and “hyper-palatable” stuff imaginable on every street corner.

For one, they sell literal American Oreo cookies and other crap. And of course they have their own brands of everything: crackers, hamburgers, hot dogs, cookies, cake.. I only checked ingredients on a couple of things I wasn’t going to eat anyway, mainly because the labels are of course in Japanese and I had to use Google Lens to translate them.

But the ingredients on their own brands of “U.S. gas station foods” didn’t seem much better than ours. Tons of emulsifiers, food coloring, soybean oil in nearly everything.

You could be going to the exact same store and eat “fast food” from a shelf, but it could either be rice and raw fish, or it could be fried chicken with soybean sauce and Oreos.

Fried Japanese Food

There’s one thing that most nutrition gurus agree on, even if they don’t think seed oils are particularly evil: avoid fried foods, especially deep fried!

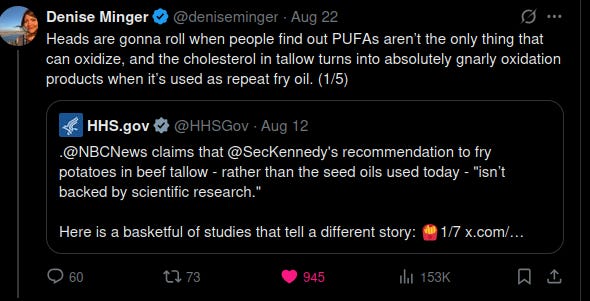

If you’re not paying attention to the esoteric health Twitterverse, hating on seed oils has become quite trendy with RFK Jr. and similar figures reaching the mainstream.

In reaction, there is now a pretty big counter-group of people who will roll their eyes and claim that, duh, it’s not that seed oils are bad, it’s just that all the junk food has seed oils and you’re using the seed oils for deep frying.

Just the other day, Denise Minger tweeted this:

In other words, people are worried about deep-frying even in absence of soybean or canola oil.

Does Japanese cuisine contain any deep-fried foods? I’m glad you asked!

There is, of course, Tempura, which just seems to be anything at all as long as it’s battered & deep-fried, e.g. shrimp or vegetables:

And there is Tonkatsu, deep-fried pork cutlet:

And there are gyoza, fried dumplings:

These are all available as fast food in the convenience stores I mentioned, and in supermarkets everywhere. There are also entire restaurants dedicated to tempura, and probably the other deep-fried foods too. For example, -katsu just seems to mean “deep fried” and besides tonkatsu there’s also fish katsu and more.

Naturally, I avoided those. I had a few gyoza once that came with a meal, but I’m not a huge dumpling guy anyway, and I avoided the tempura & -katsu type stuff completely.

Say what you want, the Japanese diet is definitely not devoid of deep-fried foods or seed oils.

So how do you answer if “Japanese food is healthy?”

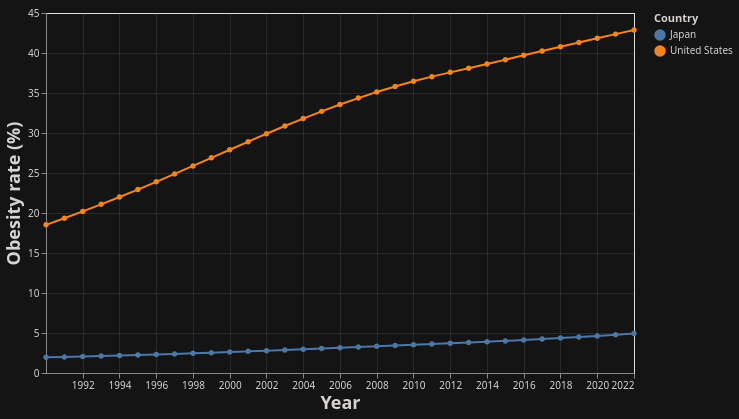

How healthy are the Japanese really?

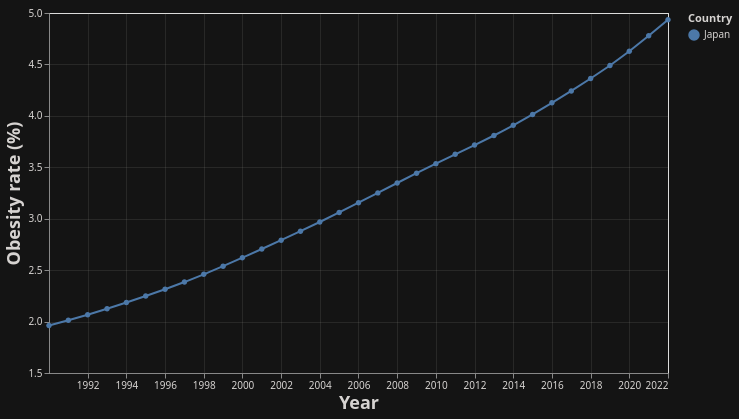

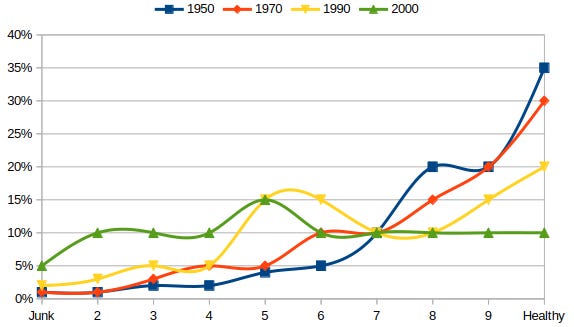

If we just look at obesity rates, the Japanese are clearly doing much better than most countries, especially similar rich countries like the U.S.:

Japan has, after long, hard work, managed to reach a 5% obesity rate. Meanwhile, we STARTED at nearly 20% in 1990, when this dataset begins, and are now honing in on 45% obesity. Good deal.

But let’s take a look at just Japan, and zoom in:

Oh my! While they’re still only at 5% obesity, it does look like it’s growing rapidly.

I can confirm this just from spending some time there. After the way some people talked about the Blue Zones and how healthy Japan was, I was slightly surprised that not everybody was extremely thin.

Sure, there are some very thin people. But as a 5% obesity rate suggests, 1 in 20 is obese - i.e. every major restaurant or cafe you visit will have at least one such person.

But obesity doesn’t tell the whole story, there are a lot of people that are “merely” overweight, including your beloved author from time to time. In the U.S., we have ~45% obesity and ~75% overweight for about a 1:1.6 ratio. I don’t know if Japan is exactly the same ratio, but it certainly could be. Just walking around, there were clearly overweight people from all age groups and walks of life. If the ratio is similar, then 1 in 20 Japanese would be obese, and about 1 in 12 would be overweight or obese.

Not to downplay that their obesity/overweight problem is obviously much less serious than ours, but the days of all Japanese being rail-thin (← Shinkansen pun!) are clearly over.

What about diabetes?

In Japan, there are an estimated 11 million people with diabetes in 2021. [1] Like much of the developed world, cases of diabetes in Japan have increased in recent times from an estimated 6.9 million people affected in 1997, to around 8.9 million in 2007,[2] to over 11 million today.

-Wikipedia on Diabetes in Japan

Japan has a population of 123.4 million people (I’m not making that number up lol), so they’re at about 9% diabetes, which is much closer to America’s rate (11.6%) than the obesity rate is.

Whatever the Japanese were doing that made them extremely healthy seems to be changing. Although their obesity rate is still quite low, they are rapidly following the U.S. in other “diseases of civilization” like diabetes.

What Japanese food do the Japanese actually eat?

So, is Japanese food healthy? Two Japanese people might be shopping at the exact same store, but one’s eating white rice with sliced fish and vegetables, whereas the other one is eating Oreos, hot dogs, and deep-fried chicken.

You might argue that this type of fried or processed “junk food” isn’t REAL Japanese food, and instead I should be living with rural farmers in Hokkaido or the Okinawans of the post-WW2 era or whatever.

But, then again, you could make that same argument for America: are KFC or Oreos really “real American food” or has the same trend of junkification and UPFification just hit America several decades earlier?

Maybe the “real” American food is grass-fed bison directly from the plains, fresh seafood from a pre-Deepwater Horizon gulf, lobster fresh off the Maine coast, or deer hunted in your backyard with your Henry lever action rifle in 1880?

My point is, of course, that merely being in Japan does not seem to make food magically healthy.

There are presumably certain things that made traditional Japanese food healthier for much longer than American food. After all, their obesity rates are much lower (although that might be genetic to a degree) and while they are getting sicker as well, they seem to be lagging behind us by several decades.

It would therefore be instructive to find out what parts of “Japanese food” made it healthy when they were super healthy, and what the changes are that are causing even the Japanese to become sicker and more overweight.

(Maybe it’s not even food. Maybe it’s blue lights or stressful jobs or EMF or microplastics in the water or pollution. But my focus is mainly on diet here, so let’s assume it’s a diet change.)

I suspect that what a Japanese grandma was eating in e.g. 1970 still exists. And that most of the “unhealthy junk” foods she would recognize, at least superficially - she would know about fried shrimp and fried cutlet and cookies, even if maybe she would’ve used a different frying oil, or not deep fried it as much, or the cookies would’ve been closer to 5 ingredients than to 20 in her day.

But, just as in the U.S. and other places, there was probably a pretty big shift in what % of the average Japanese person’s food intake was this sort of “junk food” vs. rice + some vegetables + some fish or meat, made by grandma or mom at home.

This gives me an idea for an interesting graph.

Food Availability vs. Actual Consumption

Ok, let me set this up:

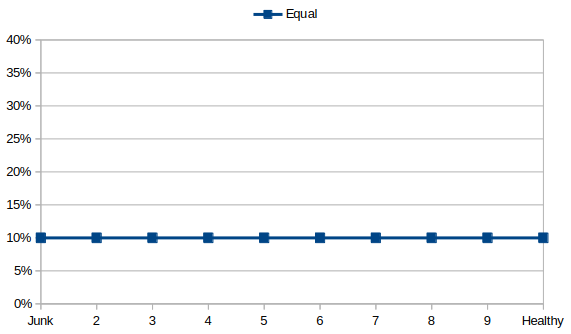

The X-axis is quality/healthiness of the food available. This could be Japan, or it could be in the U.S., or wherever. Let’s also suppose we know what exactly makes this food healthy, which of course we’re not entirely sure about. Just for sake of argument here, the food quality goes from “Junk” (1) up to “Healthy” (10).

The Y-axis shows how much of each of the levels of food quality are actually being consumed by a person or a population at any given time.

In this extremely unrealistic example, the people are eating exactly 10% from each of the 10 categories of food quality, making for a nice straight line.

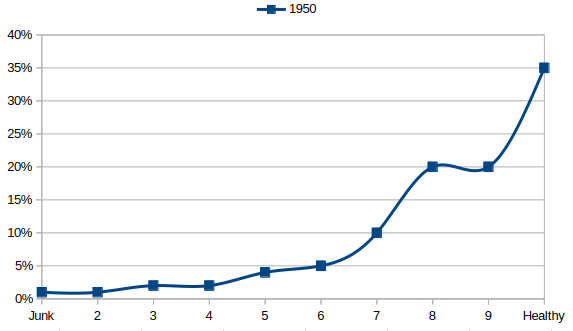

Super duper healthy 1950s food

Now let’s take a look at the 1950s. Of course I’m making these numbers up, it’s just to demonstrate the dynamic I have in mind:

The people in hypothetical 1950 are eating 35% of their food from the most “Healthy” (10) category, 20% from 9 and 8 each, only 10% from 7, and very small amounts (1%-5% each) from the 1-6 categories.

The vast majority of the area under the curve is in the 7-10 food quality range.

Remember, for the sake of argument here, the foods actually available are exactly the same. Your grandma knew about deep-fried foods and cake and ice cream. The only difference here - how much of each did she consume? The reason she didn’t eat as much junk food could’ve been price/income, cultural, health consciousness, lack of stress, more dedicated homemakers with time to cook from scratch, .. anything.

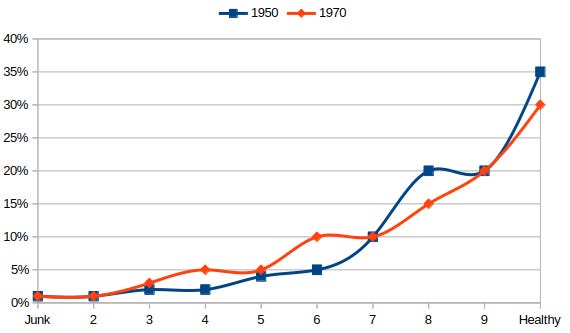

1970 - still pretty healthy

Now let’s fast forward 20 years. The food distribution is still quite healthy!

The 10 category of Healthy has only fallen by 5%, and the amount of 1-5 junk is still very low, under 5% each. But category 6 is now at 10%, and the “majority” area under the curve has moved somewhat significantly to the left.

Still, the change doesn’t look that bad yet.

1990 - problems begin to accelerate

Fast forward another 20 years. There are now way fewer dedicated homemakers, McDonald’s has switched their frying fat from beef tallow to seed oils, more and more people eat convenience foods, and fewer and fewer have learned to cook their own food.

The healthy right-hand side has now experienced a significant dent. Only 20% of foods eaten are from the healthiest 10 category, 9 has dropped to 15%, and 8 is only at 10%.

In fact, while the majority used to be in the 7-10 area, it is now actually in the 4-8 area, although the 8-10 range still has some significant exposure.

This could mean, for example, that people still eat 1 home-cooked meal a day, but they eat out or buy food at the store the rest of the day. Even with that, the food at restaurants and stores isn’t yet THAT low in quality, it’s merely “middle of the range” (4-7) instead of being healthy super high quality stuff.

2000 - Y2K crash

Having barely survived the Y2K crash, people’s habits have now changed significantly compared to the original 1950 distribution.

Compared to the last time point, 1990 (yellow line), the green 2000 line doesn’t even look that different. Sure, the 9-10 have continued to erode, and 1-5 have only increased by a bit each.

But this curve is actually remarkably close to our initial, made-up “every category is 10%” line - it’s only a bit higher at quality level 5 and a bit lower at 1 (total junk).

And if we compared to the original 1950 (blue) or even the 1970 line (red), the food actually eaten has changed very dramatically: the 7-10 section has almost entirely flattened, and the entire left (1-5) has been elevated.

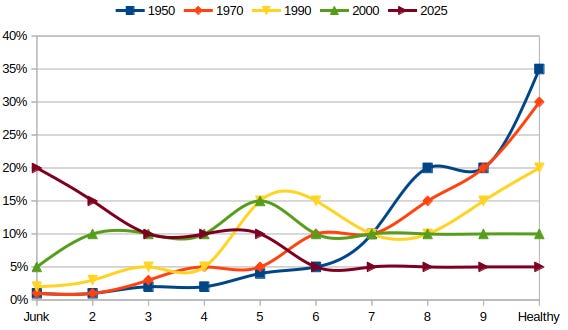

2025 - Unhealthy New World

And for our last period, let’s see what happened in another 25 years. (Did I mention that I’ve just made these numbers up to illustrate a point?)

The right half of the graph has dropped further, only by 5% but consistently. The left half has increased to make up for it, with the very unhealthy (1-3) categories now very prominent, the highest peaks. 1-3 could represent people eating total junk food at restaurants, e.g. fried chicken w/ soybean oil sauce and soybean oil-containing biscuits, and half a gallon of Mountain Dew as a drink.

There’s still a lot of volume from 3-6, which could be not-quite-total-junk-but-not-particularly-healthy foods grabbed at restaurants or in stores. This could e.g. be salads which look healthy but contain soybean oil dressing, or chicken/pork that isn’t fried but from animals fed soybean and corn meal, or a facsimile of a healthy old-school food but made with faux ingredients, e.g. bread with 20 ingredients, or re-constituted yogurt-like substances.

People also still eat some amounts of pretty healthy stuff, but the entirety of the 7-10 category only adds up to 20%. This could be getting lucky at Whole Foods, or actually making your own bread from scratch once a month, or your grandma cooking for you on the weekends, or whatever.

But the vast majority of people’s food intake is from the 1-5 categories, where “It’s not a total junk food if you squint” is as good as it gets.

Going Forward - Total Apocalypse

I’ll spare you the 2050 projection. tl;dr: it’ll all be deep-fried red dye 40 emulsified with carrageenan. Microplastics will be the healthiest food people eat.

I hope these graphs help you visualize how, even with the exact same healthy & unhealthy foods “known” or “available” to you and your grandma, just counting what’s available in a store might not give you a good impression of what people are actually eating, and what they were eating in the past.

I made these numbers & decades up with the American diet in mind. For Japan you’d probably have to shift the entire sequence back by 20 years.

For example, like I mentioned, it’s quite common to see people buy & eat sushi and onigiri in convenience stores in Japan, and I suspect that the high-quality, healthy 8-10 categories are way more common than they are in the U.S., just for cultural reasons and pride in their cuisine.

So, what do the Japanese ACTUALLY eat? I suspect it’s probably closer to 1990s or even 1970s America. But clearly they’re not eating the same things they used to, as their health trends indicate.

Conclusion

Visit Japan. I’m serious, it’s very interesting & you’ll have a good time. Definitely try the Shinkansen too hard ice cream while the beautiful rural Japanese landscape rushes past you at an insane speed.

As for myself, after a week of eating delicious Japanese food, I just.. went back on ex150. Turns out they have excellent single-ingredient cream with no emulsifiers from Hokkaido, an island in Northern Japan that seems to be a big agricultural producer.

On day 2 of ex150-15, I’m already down 7.5lbs from the salty peak.

I’ll return home in a couple of days, finish the rest of ex150-15 there, and think of a new experiment to try in the meantime.

This makes me think about what the Snake Diet guy is now demanding of his clients, which is to ditch the scale entirely. He's pushing an old-school bodybuilder diet: chicken breast / white fish / round steak, and potatoes or rice, and veggies and fruit, all with loads of added salt.

The scale thing is the most interesting to me, because in the grand scheme of things you and I aren't even that big of guys, not even close really, but I had a similar blowup a couple weeks ago, almost 15 lbs within 2 days - not even that dramatic of an eating shift, either, and one that surely would end up producing fat loss over time. Its hard to take those weight shocks in stride and not over-correct, restrict food, or if you have less discipline/experience, crash out and binge.

Personally I'm doing none of the above at the moment, my bachelor party is in 5 days and wedding in 12, so I'm water fasting ATM, kill me. Enjoy some onigiri for me

Nice article! I went to Japan recently, and all I can say is yes to everything you've said: go there, try the food, take public transportation, take the shinkansen. Specifically about food price, Japan's food is cheaper than France, especially with the exchange rate. Especially convenience store stuff, in France there's some kind of "cheap food ready to eat will be terrible or pricey". Same for the location, in France a bottle of water in a train station will run you 3€ instead of 1€ in the supermarket, in Japan it'll be something like 130 yen in the vending machine in the train station instead of 120 everywhere else, and maybe 140 yen at the airport right next to your boarding gate.

Your graphs kind of make sense, and remind me of the people that did well on "mostly potato diet" (riff trials I think?) or the person on twitter that either you mentioned or talked to you about doing well on mostly exfatloss but not as strict as you. Seems like you in particular are more vulnerable to moving away from a strict diet. I have no idea what could explain that and how much it could be measure in people.