Book review: The End of Craving

The End of Craving by Mark Schatzker is not a bad book, but I wish it stuck to its meat & potatoes

A while ago, somebody in the comments recommended The End of Craving by Mark Schatzker. I finally got around to reading it.

In short, I think there are 5 reasons to read it:

It explains large swaths of nutrition/dieting history well and concisely

It investigates the hypothesis that “enrichment” or “fortification” of basic food ingredients, as done in the U.S. and some other countries, could be problematic

It explains the current thinking of desire, dopamine, reward systems, etc. in a clever model that I had not heard of

It explains in great detail the horrible “food simulacra” we’re exposed to, or how the UPF sausage is made

It is relatively short

The last bullet point is sort of a giveaway. I love reading. But this book should’ve been 3 papers of a handful of pages each.

The author has apparently written books called The Dorito Effect and Steak: One Man’s Serch for the World’s Tastiest Piece of Beef.

Unfortunately, the level of the book is somewhat as expected: Malcom Gladwell level journalisming. Meaning it’s a decent broad view, but shallow on details. Often times, I got the impression that the author didn’t really understand the concept he was explaining.

Like someone pretending to be a programmer might say “I was just writing some codes” he often says things suspiciously verbatim, or wrapped in such a layer of metaphor & flowery language that it would make a wild honey bee blush.

Still, it’s not a bad book. It does contain several ideas that I hadn’t heard before, and some in a level of detail that I was not familiar with.

If I had to take a guess, I think the author had about 50-100 pages worth of material, and then realized that you can’t publish a book with less than 200 pages for some reason.

Then he probably proceeded to fluff & stuff the material until he just barely scraped over the finish line at 204 pages.

Great Overview

The first part is a great overview over the recent history of dietary thought on the subject of obesity et la. It explores:

Low-fat

Low-carb

Low-sugar

CICO

And how none of these seem to have solved anything. Instead we’ve gotten fatter and fatter despite dieting harder and harder.

The level of detail here isn’t great enough to convince a die-hard adherent of one of these diets that he is wrong. But I think that if you just want a quick overview, it’s a pretty fair analysis.

I am a massive ketard myself, but even I admit that Keto has largely failed for obesity.

Everyone honest will admit that none of the paradigms or ideas listed above work effortlessly & amazingly for all people. Some work for some people some of the time.

Fordified Foods

(This is a conveyor belt pun.)

I’ve said for a while now that I don’t believe in micronutrients. I say it half-jokingly.

The main point is that our understanding of them seems to be so bad as to be largely counter-productive. We have so many false positives and false negatives that we would be better off pretending we knew nothing at all.

Examples:

The RDAs on many micronutrients like vitamin C and vitamin A are clearly completely wrong, and people can live & even thrive on a tiny fraction. There are tens of thousands of carnivores out there, some having eaten only meat for decades. None of them seem to develop scurvy unless they restrict their meat intake to processed meat or pemmican. Any amount of fresh meat seems to be enough vitamin C. Similarly, there are people who have actively tried to eat as little vitamin A as possible for a decade, testing at near-zero and “chronically deficient,” without seeing any of the alleged vitamin A deficiency symptoms one would expect after only a few weeks.

The RDAs pretend there is no context for micronutrient requirements, which is clearly false. E.g. keto/carnivore people appear to require magnitudes less vitamin C than high-carb eaters, and this might be true for some B vitamins as well

Lots of foods that are “known to be” void of a specific micronutrient, and are even listed as such in the USDA database, do in fact have large enough amounts that eating them prevents any deficiencies. E.g. meat, which does contain vitamin C in amounts high enough to sustain carnivores at least, is often listed as 0 vitamin C. Sometimes there’s an asterisk telling you the 0 value is “assumed.”

We pretend that micronutrient deficiencies are solely caused by lack of nutrient intake, instead of sufficient intake and then insufficient or broken metabolizing/absorption of said nutrient in the body

We pretend that there is no upper limit or downside to excess micronutrient intake. There are upper limits, but if you even mention them, you often get laughed at or straw man arguments are brought up at best. There are known acute toxicity limits for vitamin A, C, and D that I know of, probably more. Even if you don’t keel over from a single dose, some (mostly fat-soluble) vitamins can accumulate in your body and eventually cause problems. For example, it’s trivial to go over the safe recommended dose of vitamin A from eating dairy, tomatoes (especially concentrated sources like sauce), less than 2oz of beef liver (!), eggs, or a single sweet potato. I’ve been above the limit myself for almost the entirety of the last 3 years, just from my heavy cream intake, and one month from the tomato sauce I put on my rice. It’s not 100 gallons of tomato sauce, a big jar will probably put you over the limit.

All that said, I was very open to the idea that “enriching” or “fortifying” base food ingredients with CHEMICALS (*cough* vitamins are just chemicals too *cough*) might not be a genius idea.

Much of my normal heavy cream diet is not fortified. Cream doesn’t appear to be fortified, probably because it isn’t consumed in high enough quantities. Milk, and especially skim milk, is heavily fortified.

Flour is fortified, sugar is fortified, rice is fortified. Seed oils are fortified with vitamin E, I believe.

Organic foods are apparently excluded from the law, and thus may be non-fortified. Some brands will proudly advertise this. When I did my rice diet, for example, I would opt for more expensive, organic rice that was not fortified (Lundberg brand).

Honestly, I just don’t trust food scientists to do more good than harm. Maybe they got this one right, but I’d be surprised. They seem to have been wrong about so much else.

Why We Fortify

The US isn’t the only country that fortifies its base food ingredients, but not all of them do it. The idea was that lots of poor people in the early 1900s would get micronutrient deficiencies like pellagra.

Pellagra is apparently an Italian word and means “weakness.” People who ate lots of certain staples like corn would get enough energy and protein from their food, but they would be lacking a certain micronutrient. This would eventually cause severe health problems, including skin issues, then weakness, and culminate in death.

The sickness was well-known in both the US and Europe and probably other places for centuries, but the missing ingredient was only discovered somewhat a little over 100 years ago in 1915: niacin, or vitamin B3.

Until this was addressed, millions of Americans, mostly poor Southerners, got pellagra, with over a hundred thousand dead in total.

How did we address it? This is the point the book is trying to make.

In the US, we began mandating by law that niacin be added to staple foods like corn, rice, flour, and sugar. Eventually, we added other vitamins too, like riboflavin.

That’s why, if you look at the ingredients of a typical American loaf of bread, you see this shit:

The wheat flour has been “enriched” with niacin (B3), iron, thiamine (B1), riboflavin (B2), and folic acid (B9).

The Italians, who were also big corn-enjoyers and who similarly suffered from a pellagra epidemic in the early 1900s, went a “different road” as the book calls it.

They mandated, by law, that people share whole wheat bread in their towns, gave financial incentives to grow other crops known to contain these vitamins, and so on.

But they did not add random chemicals to their staple foods. To this day, apparently, they do not fortify any foods.

And nowadays, of course, it wouldn’t be needed: nobody in the US is lacking B vitamins. Nobody’s poor enough to subsist on only corn for months at a time.

Did vitermins really do obesity?

Plenty of countries don’t fortify their staple foods at all and do plenty fine.

Or, if the author is to be believed, they do better.

Although I am skeptical of fortification, I am not quite convinced it is THE reason for the obesity epidemic.

For one, there are plenty of countries that do not fortify at all and that still see a rise in obesity, or even an epidemic.

Secondly, you can actually evade most or all fortification. Like I said above, you can buy non-fortified organic foods.

But even better, you don’t have to buy any of these staple carbs at all. If you do a paleo-esque diet of fresh fruit, vegetables, and meats, you’re not eating ANY processed or refined grains or sugars. If you skip the skim milk (and many variants of paleo are against dairy anyway) then you won’t get nearly any fortification in your food supply.

I did paleo myself for years, in which I would’ve gotten very low levels of fortified micronutrients, and I never lost any serious weight on it.

Italy vs. USA: not the dream world cup semi finals

The other thing is, the US vs. Italy comparison doesn’t hold up quite that well.

Of course, the US is much fatter & sicker than Italy, no doubt.

But have you been to Italy? I’ve vacationed there several times, and I can tell you from personal experience that there are plenty of fat people in Italy, even obese ones.

They also have lots of heart disease as well. Their diabetes rate clocked in around 8% in 2024, only 1-2% below ours.

If you look at the WHO list of countries ranked by obesity, Italy is not doing terrible at 114 out of 191 countries, but it’s not even stellar within Europe. Italy has an obesity rate of 24.12%, whereas Norway is 23.4%, Spain 22.08%, Netherlands 20.5%, Austria 20.36%, Sweden 19.85%, Denmark 16.63%, Switzerland 16.05%, France at 12.36%..

There are certainly countries much more obese than Italy, even in Europe. But they clearly have not escaped the obesity epidemic in totality by refusing to dump B vitamins into their ingredients.

Now of course it’s difficult to compare entire countries. There is no one diet in a country, the data is extremely difficult to capture.

But at the same time, that makes it difficult to say “Italy doesn’t fortify their flour, that’s why they’re thinner.”

A similar line of thinking I often encounter is “the Japanese eat lots of fish and I like Toyota, ergo omega-3 fats are healthy.”

If I were a betting man, I’d say that vitamin fortification is probably at best a part of the problem.

Of course, if you made me dictator for a day, I would still get rid of it. This isn’t 1902. Nobody’s getting pellagra in this country.

The Itchy & Scratchy Show

The most interesting part of the book, to me, was the section on the reward system.

I vaguely knew words like “dopamine” and “food reward” and “Pavlovian conditioning” and so on, but this explanation puts a pretty cool spin on it that explains certain things much better than I’ve ever seen them explained.

In short, apparently scientists were looking for the mechanism of “desire” or “reward” in our brain forever, and it seemed sort of paradoxical. Lots of mice had their heads rewired in weird experiments, but they finally came up with a pretty cool explanation:

There are TWO types of signals in the reward system, not just one.

The first one is what the author calls “wanting” and which you would recognize as anticipation, craving, lusting, desire, and so on. This is driven by dopamine. Dopamine is hence not a “pleasure” hormone but a “drive” or “desire” hormone.

The second one is the actual fulfillment once the goal is reached. This is the reward. It turns out not all animals have big food reward signals like us. Apparently many carnivores, e.g. snakes don’t really have a sense of taste - because they don’t need it. Pretty much anything a snake will eat is good for the snake. It doesn’t need to detect poison mushrooms, bitter greens, or unripe bananas, like an omnivore would.

Schatzker calls this “the omnivore’s dilemma” (I know there’s a book with that title, but haven’t read it. I think it’s unrelated). The idea is basically that an omnivore can eat pretty much everything, but how you combine foods is important. You require a bit of this and a bit of that. If you eat too much corn, you get pellagra. If you eat only tallow, you get sarcopenia from lack of protein. If you only eat green vegetables, you strave from lack of energy (unless you’re a ruminant). You only eat white rice, you get beri beri (lack of B1, similar to pellagra).

As an omnivore, it actually matters WHAT you eat, and that’s what our enjoyment of food is really for: to condition us to chase the correct foods, not just ANY foods.

You can think of these 2 signals as an itch and a scratch, or the relief you experience upon finally scratching that itch.

The distinction into these 2 helps explain some phenomena that would otherwise be pretty paradoxical, e.g. addiction.

If you have a very strong drive to take a drug, but you don’t get any relief from taking it, you are essentially addicted. You will keep chasing that high, but relief never really comes in the sense that you desire.

In a functional system, the two signals are synchronized: if you have a strong drive to achieve something, it should give you a great deal of satisfaction once you “scratch” that “itch.”

A mismatch between the signals is really the problem. If you have a very strong drive but not a lot of satisfaction from reaching your goal, you’re “addicted.” The book goes into gambling and how casinos explicitly abuse this mismatch in gamblers.

Presumably there is also the opposite situation, in which you’re not very driven to do something yet it gives you massive satisfaction. He doesn’t go into this, and I honestly can’t think of an example. So maybe it’s rare or not possible.

This 2-signal reward system and addiction is a great setup for the rest of the book, because it is much better at explaining “ultra-processed foods” and their inherent problems than anything else I’ve seen or read.

Super Nova

The author doesn’t really use the Ultra Processed Food (UPF) terminology that seems to center around the stupid NOVA classification of food processing.

I think that’s a very good thing.

Personally, I think the term “ultra-processed food” or even worse just “processed food” is a terrible misnomer. It’s an incorrect intuition pump and leads people to wrong conclusions almost 100% of the time.

What is so unhealthy about “ultra-processed” food? The name sounds like it’s just more processing. What makes food “processed?” All food is processed - it’s plucked, shot, hunted, butchered, dried, canned, sliced, cut, packaged, mixed, cooked.

Are all of these bad? Are canned beans worse than uncanned beans? Are cooked beans worse than raw beans? Is dried meat worse than fresh meat?

I believe that “ultra-processed food” is an entirely different category from “regularly processed” food. Describing them all with an increasing classification system like NOVA is as silly as sorting modes of travel like this:

Unassisted travel: Foot, bicycle

Lightly assisted travel: Car, motorcycle

Very assisted travel: airplanes, helicopters

Ultra-assisted travel: Spaceflight

If you gave somebody this classification, he’d get the impression that he could fly to the moon on a bicycle and it would just take a bit longer.

That’d be quite misleading. Flying to space is an entirely different endeavour (heh).

Ultra Processed Foods are Simulacra

When you look at the foods typically classified as “ultra-processed foods” or UPF, they are qualitatively different. It’s not beans that are dried and sliced and canned AND cooked, or then mixed with olive oil.

The malignant UPFs are not even really foods in the usual sense.

Foods, for most of history, have been certain pieces of plants or animals occurring in nature. We then did some light processing to them to make them edible & palatable: we butchered the animal. We pounded the grains. We peeled the fruit.

Then we might’ve done some more processing: cut the fruit into slices, cut the meat into steaks or grind it into ground beef. Maybe de-husked the grain or soaked it or what have you. At the end, we’d probably cook it, because we cook most of our starches & animal products and pretty much only eat fruit raw. Some foods would be made longer lasting by drying (beef jerky/pemmican/dried fruit) or smoking (sausage) or canning. (Is frozen food “processed?”)

UPFs, on the other hand, are nothing of the sort. They are designed and manufactured out of nothing. There is no oreo plant or dorito plant in nature. These are simulacra, concocted by combining various industrial food components like starches, fats, fat-emulators, emulsifiers, flavors, and so on to create something resembling a food we already know - a cookie.

The whole thing reminds me of a description that Stephen King (God rest his soul) gives in his book On Writing about Christine, the namesake “evil killer car” of his horror novel.

I’m going to paraphrase because I don’t have On Writing handy and it’s been about 10 years since I last read it, but it goes something like this:

Christine is a replica of a car as if it was built by someone who has never driven a car. Maybe an alien who doesn’t know what cars actually do or how they function.

It has wheels and lights and a steering wheel and seats, but the angle of the steering wheel will probably not seem quite right. The wheels might be in weird spots or the number might be too big or small. The lights might be present, but pointed in the wrong direction, or there might be useless duplicate lights that don’t seem functional.

There would be buttons in the car, but they wouldn’t necessarily connec to anything useful; there might be buttons that don’t seem to do anything, and important buttons might be missing.

In short, Christine might seem car-like, but it is clearly not a car.

Ultra-processed foods are like this. They have a physical shape that probably approximates a “food” we know. They often simulate flavors from nature (except Mountain Dew, which simulates the flavor of becoming the Joker). They are designed to resemble real foods, but they are not, in fact, real foods in that sense that we take something from nature and cut it up and can and cook it.

One might say that UPFs are designed to be addictive, or hyper-palatable, as cheap as possible, to make use of industrial waste products like whey protein or maltodextrin.

Leaving that aside for a second, I do think they are an entirely different class of “food” from regularly-processed food like “dried beans” and “beef jerky” and “sliced apple w/ syrup” or even “white bread.”

I suppose you can include them in the definition of “food” since we can put them in our mouths and they don’t come out the other side completely undigested. But they’re in a completely different class to what we historically called food.

I thus wish the UPF people would come up with a classification that has “real foods from nature, processed in some way, maybe less or more” vs. “designed from the ground up and put together by combining various food chemicals.”

The NOVA classification is simply misleading.

Industrial Food Atoms

The book devotes quite a bit of time to the individual ingredients many modern food simulacra are made of. You’ll recognize many of them from nutrition labels.

But despite being pretty skeptical of added ingredients and mystery names on my food labels, I was surprised by how broad & deep this rabbit hole goes.

Here are some of the industrial ingredients used to create “food simulacra”:

Creamfiber 7000: invokes the taste of fat without any fat

Saccharin/stevia/etc: artificial sweeteners

Bitter blockers: to counter the bitter, lingering taste of some artificial sweeteners

Xylitol/maltitol/isomalt: low-caloric sugar alcohols to replace sugar

Simplesse and other “fat replacers”: whey protein chemically altered to give a creamy, fatty texture in absence of any actual fat in the food

Slendid/CrystaLean/Lorelite/D-LITE : bulking & thickening agents

Avicel/methocel/Solka-Floc/Genutine: increase mouthfeel and “flow”

Maltodextrin and other “modified starches”: to add bulk & prevent ingredients in cream, ice cream, or yogurt from separating

Flavorings: used to simulate the flavor of natural or even artificial foods, e.g. used in “berry” flavored yogurt. There might not be real berries in it.

What’s very sneaky is that many of these super chemical & unnatural sounding industrial ingredients are listed with more innocuous and natural sounding names on the packaging.

For example:

Simpless goes by “milk protein” or “whey protein concentrate”

Genutine and other texture agents go by “carrageenan”

Creamfiber 7000 is listed as “citrus fiber” on the label

You cannot simply add 1 of these and be done. To really simulate the flavor, texture, taste, and overall experience of eating natural yogurt, or whipped cream, or butter, you have to combine a whole bunch of them.

You need to invoke the creamy fattiness that coats your tongue for a few seconds. The flavor. The texture and gel-like chewiness. You need to add bulk if solid or whipped fat is being simulated, so you use maltodextrin. To make it sweet, since you don’t have natural lactose or fruit sugar, you add a sweetener. To cover up the bitter aftertaste of the sweetener, you add a bitter blocker. And so on.

In this way you can today buy “berry yogurt” in the supermarket that doesn’t contain any yogurt, any sugar, or any berries. Hence, 100% of the simulated ingredients are missing. This is not a natural berry yogurt in which some ingredients have been swapped out; it’s a food simulacrum entirely created from scratch by combining various non-food industrial ingredients in a way to trick your taste buds.

Food Simulacra don’t even taste better

I was just talking about this with my friend John over at The Heart Attack Diet.

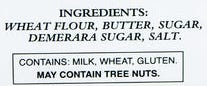

These frankenfoods don’t even taste better! I have recently really gotten into Walker’s Scottish Shortbread. (In case you’re not Scottish, it’s just butter cookies.)

Here are the ingredients:

Now this is how my grandma would make cookies or cake. Flour, butter, sugar, and salt. It’s basically pound cake.

This is an honest to God cookie. It has real flour for flavor, texture, bulk, & crunchiness. It has real sugar for texture & sweetness. It has butter for the texture & melt-on-your-tongue feeling that fat gives you. I’m not a baker, but I presume the salt somehow creates a more interesting contrast when combined with sugar.

The thing is, these 5-ingredients cookies taste MUCH BETTER than any Oreo I’ve ever had. The frankenstein food simulacra in the modern American supermarket don’t even taste good if we’re honest.

Are they cheaper? Maybe to produce, I couldn’t tell you. But I’d much rather eat a 150g box of Walker’s Shortbread than a 2lbs box of Dorito-Mint flavored Oreos.

The shelf life? Maybe it’s longer, I don’t know. But they apparently manage to produce this short bread in Scotland, ship it over the pond to America, drive it to my local supermarket in a semi truck, and then it sits in the “Ethnic Food” aisle until I show up to buy it for a refeed. How long did that whole process take? I’m guessing at least 3 weeks. They’d probably last years.

So what’s the advantage of creating these insane industrial frankenfoods? Are we just creating employment for food scientists? Maybe we could have them dig some holes and fill them back in again, at least that wouldn’t mess with our food supply & health.

Food Simulacra taste like shit - but they’re Hyper-Palatable

The book doesn’t really go into the difference much, in fact the author seems to conflate hyper-palatable with “delicious.”

I think “hyper-palatable” is another one of those terms that are poorly chosen. “Palatable” means “tastes good” and you’d think “hyper-palatabale” means “tastes extremely good.”

Yet nobody would argue that peanut butter crunch chip mint dorito flavored Oreos or cinnamon flavored cheetos taste better than your grandma’s pound cake.

Nobody would argue that Domino’s pizza tastes better than an Italian grandma’s homemade pizza.

It’s insanity to argue that modern french fries are nearly as good as even the ones they made 30 years ago in tallow, from fresh cut potatoes.

But that’s not what food scientists and nutritionists mean by “hyper-palatable.”

Hyper-palatable really just means that these foods induce over-eating by stimulating certain pathways in your body & brain.

You could say these foods are designed to be “addictive” but I don’t really like that word. It’s pretty badly defined, subjective, “I know it when I see it.”

Many people argue that evil big-company food scientists are lurking in their labs, designing food simulacra to be addictive, to fool stupid little you into overeating them.

But this book makes the case that these frankenfoods don’t necessarily have to be designed with evil intent in mind, but that overeating them is a logical outcome of creating food simulacra in the first place.

Mismatch

Now, we finally get to the real thesis of the book. We’ve set it up with the dual-signal reward system of “itches” and “scratches.” We’ve learned about staple foods fortified with vitamins and minerals. We’ve learned about the food simulacra and the very weird & tricky ingredients - no, chemicals - they’re made of.

I will say that I am not 100% sure I believe this thesis, or at least I don’t believe it’s necessarily the root of the obesity crisis. But it might contribute, and it’s a great reason to avoid food-like creations form commercial designers & producers of frankenfoods.

The idea, and he shows various studies to prove it, is that these food simulacra don’t necessarily trick you into overeating directly.

If you were an evil food scientist looking to make people fat, and you believed in the naive “eat more empty carolies, get fat” theory of obesity, what would you do?

Well, of course you’d put a bunch of carolies into a food and you’d make it taste LESS intense. That way, to get the same level of “food pleasure” from a fake cookie, consumers would have to eat 2 cookies instead of 1. They’d have to buy a bigger tub of fake-yogurt.

But many of these frankenfoods are actually the opposite; they are “hyper-palatable”: they trigger our food senses way more intensely than most or any natural foods.

Most American fast food & candy is so intense and overflavored that first-time visitors can barely tolerate them. If you hand a pumpkin spice mint frappuccino, or a bag of doritos, or Mint Chocolate Oreos to a European, especially an older one, he can barely get any of that stuff down.

Nobody in the world thinks our food is “the most delicious.” In fact, people think American fast food is a laughing stock. It tastes bad, and we’re STILL so fat. It must be a sign of moral defect. Imagine how fat Americans were if their fast food tasted as good as Italian homestyle cooking, or French haute cuisine!

But, the author argues, this actually makes sense. Because it’s not about “more calories per flavor” but instead nutrient mismatch, or “confusion.”

Historically, if a food contained more sugar, it was sweeter. If it contained more of a certain ingredient, you could taste that. Your brain could therefore make sense of the food environment, and gauge how much and of what you should eat (remember the “Omnivore’s dilemma”).

But with modern faux-ingredients, we can create the “same” food with completely arbitrary ingredients.

Imagine the following:

Full-fat yogurt created from real milk, with real berries: has fat, has sugar. Is creamy, gel-like, bulky, and sweet. Has, say, 400kcal per serving.

Yogurt with texture & bulk from maltrodextrin, gel-ness & tongue feel from Creamfiber 7000, sweetness from stevia, the bitterness overpowered by a bitter blocker, whey protein for that pearly fat-feel on your tongue, and artificial berry flavorings

You could make the latter food simulacrum with nearly 0 calories, or any number of calories you want.

And many of these products were actually made with lower calories specifically for diet reasons. The low-fat crazy of the 80s and 90s was a huge push here. Food scientists might’ve thought they were actively doing good by replacing the “fattening” fat in yogurt, butter, cake, pastries, and other food. Management didn’t complain since it was cheaper. Win-win, right?

And once we all got around to thinking sugar was fattening, they did the same for sugar and we now have infinite types and variants of artificial sweeteners.

All the time, food scientists managed to create frankenfoods that vaguely resembled the original food, yet contained less and less sugar and fat.

The outcome was that modern food simulacra taste way worse than the real foods they replaced & simulated, but one thing changed dramatically:

Our brains are now no longer able to determine what is in these “foods” from flavor. It would seem that “berry yogurt” contains sugar and fat and berries, but that is no longer so. It might contain anything. It might be virtually fat free, and sugar free, only deriving its texture & flavor from artificial ingredients tricking your body by pressing certain “flavor” and “texture” buttons.

I get the impression that we don’t know why exactly uncertainty creates this “addiction” but they speculate that it creates a false sense of famine.

The book lists a couple of interesting experiments on food uncertainty and how it induces overeating. These experiments are typically done on rats. The rat can press a lever to receive a piece of food, but the levers are programmed differently.

A rat that always gets food upon pressing the lever has certainty, a stable food environment. It doesn’t need to worry about starvation.

But in another arm of the experiment, the lever only sometimes works. The rat thus doesn’t have food stability - if it can’t be 100% sure it’ll get fed, maybe this was the last time the lever rewarded it with food? Better stock up, just in case!

The interesting case is that the rats can be tricked this way even though there is actually enough nutrition available, in absolute terms.

Despite having more than enough food, the added uncertainty of the tricky lever causes them to eat more than they otherwise would.

The idea is thus that our “sense of uncertainty & potential famine” is not triggered by actual, objective lack of food, but by the uncertainty itself. This could make evolutionary sense: you don’t want to become aware of a famine when you’re starting to starve. You want to be prepared, and be on top of your game while you still have a chance to stock up, as soon as the first signs of potential famine arrive.

Gambling with our Food

So how does this lead to obesity?

Schatzker likens it to gambling. The way you get people addicted to gambling is not by rewarding an activity (like pulling the lever of a one-armed bandit) every time. Nor is it by never rewarding it.

The trick that casinos use to make you addicted is uncertainty. You pull the lever precisely because you don’t know what’s gonna happen. You might lose, you might scrape by, you might win big.

This has been replicated in the animal experiments. Let’s look at the rats with the lever that will reward them with food every time. They’ll press the lever until they’re satiated and then do something else.

But if you give them the lever that SOMETIMES rewards them with food, they’ll become addicted.

Something about the uncertainty between the “itch” and the “scratch” seems to drive what we would term “addiction”: repetitive behavior that can have severe negative consequences, like gambling away your home, or becoming a drug or food addict.

The thesis Schatzker promotes is essentially that the disconnect between the flavors and carolic/nutrient content of modern foods causes us to perceive scarcity, and leads us to overeat.

Even in absence of evil intentions by the Big Food Scientists, this might create “food gambling addiction” in us. Our brains might be pressing that lever over and over, beyond the actual requirements of macro and micronutrients, because we are being tricked by uncertainty into believing that a famine is coming.

The uncertainty lever in our case: faux foods that sometimes contain 400kcal, sometimes 200kcal, and sometimes nearly 0kcal, for what looks and somewhat tastes like the exact same food.

Does this explain mono diets?

An interesting thought that’s not in the book, but that immediately came to me: does this mean that, independent of metabolic fuckery or evil, laughing, mustache-twirling Big Food Scientists, a certain amount of food variety is necessarily confusing to our metabolism?

There are at least 2 phenomena that immediately come to mind. One is increased food variety from globalization, the other is mono diets.

Mono diets, like the potato diet, Kempner’s rice diet, or frankly my own heavy cream diet, are often “miraculous” for fat loss in many people.

One common argument is that “Duh, you’re only eating 1 thing! It’s so boring of course you eat less.”

I don’t really buy that argument; for one, my diet is absolute delicious. Second, I have actually measured my carolies and I eat a pretty healthy amount of carolies, generally around 3,300kcal/day. I’m certainly not unknowingly starving myself.

But it could be that a sort of opposite thing is the case: it’s not that the mono diet “makes you eat less” but that a variety of foods makes you eat more.

Not just in terms of increased variety, sensory experience, etc. It could be that your brain just needs to re-train what macro/micronutrients it’s getting and how much of which foods you should be eating.

If you think about it, food choices were way more limited even when I was a kid in the 90s. My grandparents wouldn’t have had fresh strawberries from New Zealand, imported cassava from Africa, Quinoa from wherever the heck that abomination is from, and so on.

The food eaten by most people, even richer people in the West, even just 1 generation ago, would’ve been pretty boring by our modern standards. Way less Vietnamese-Mexican Fusion food trucks.

You would’ve probably eaten the same thing as most people in your town or neighborhood or even county. It would’ve changed, but mostly with the seasons, and very slowly. It might’ve had more seafood if you lived near the coast.

You didn’t necessarily eat a mono-diet, but you would’ve probably eaten a mono-cuisine diet. You didn’t have the choice between authentic Italian homestyle, Mexican-Asian fusion, American diner fare, Ethiopian spongebread (whatever they call it), sushi, Korean BBQ, Indian food, and more all in one city block.

You’d have eaten the cuisine of the region you grew up in. Maybe a big city like New York City would’ve offered more variety than Dodge City, Kansas.

But the vast majority of people would have eaten a very boring diet most of their lives by our modern standards.

In that sense, maybe there is something special about limiting your food choices, even if it’s not a full-on potato diet. Maybe having month-long “phases” or even “seasons” of eating gives our brain time to re-learn the new food & nutrient environment we’ve suddenly put ourselves in.

Fortify & Confuse

This “nutrient confusion” is also part of why fortification & enrichment may actually be bad for us in the long run.

Even if these added vitamins & minerals might’ve cured pellagra in the 1940s, they seem to lead to an overload of these micronutrients in the modern age. Almost everything we eat is “enriched & fortified”: flour, rice, sugar, seed oils, dairy.

There are minimums about how much gets added, but no upper limits. More is better.

Most of us modern people already get enough micronutrients from our food because we are not poor Southerners or Italians subsisting solely on corn.

Yet all of these things are added on top.

The magic word “vitamin!” somehow tricks us into thinking that it couldn’t possibly have any downside

Schatzker’s thesis about why this is bad shows some impressive studies: you can actually fatten up animals by adding vitamins to their diets, especially B vitamins.

In animal husbandry this is apparently used to fatten up pigs. They used to have to keep the pigs outside on the pasture. Just feeding them corn & soy in a confined cage would make them sick and they would die. Some micronutrients were missing, and letting them out onto the pasture gave them the opportunity to scavenge the right foods that contained these micronutrients.

But now, you can just add B vitamins to the soy/corn feed, keep the pigs in cages, and they’ll fatten up much quicker than those not fed the B vitamins.

The author is basically suggesting that this might happen in humans: we used to have to “go out onto the pasture” to get all our micronutrients needs, and thus to fulfill all our “appetites” for different vitamins or minerals.

These days, base ingredients like flour, rice, sugar, and dairy are enriched/fortified. This in effect turns us into those confined pigs in their little pens, who gain weight more quickly than those that had to pick & choose from nature’s offerings to get the right mix of micronutrients.

If I’m honest, I’m not quite sure I understand the suggested mechanism here. I get that the study shows “pigs in pens w/ B vitamins gain fat more rapidly than those w/o B vitamins, and those on the pasture were even leaner.”

But it’s kind of confusing, or the reverse of what I’d expect from the “nutrient confusion” here.

You’d think that if we have different “senses” or “appetites” for all the macro and micronutrients we need, eating flour fortified with vitamins would make us eat LESS than flour not fortified. After all, in absence of fortification, we’d presumably still eat the same amounts of flour (for the “energy appetite”) but would also have to eat, say, an apple for vitamin C or a steak for B vitamins?

I suppose you could make some argument that the “calories per vitamin” in flour/sugar are higher than they would be in apples or steaks, but I’m not necessarily sure that’s true.

And even if, couldn’t we just give people vitamin pills then? Why wouldn’t multivitamins fulfill people’s “vitamin appetites” and make them stop eating the fortified flour/sugar?

What’s more likely, in my opinion, is that this is less about the fortified vitamins being vitamins, and more just about the biochemical effects certain ones of them have.

For example, the relevant vitamins in the pig pen study were B vitamins.

Many B vitamins are known to be important cofactors in energy production in the Krebs cycle.

Schatzker talks about this briefly, but again in a way that didn’t intuitively make sense to me. He’s suggesting that, in absence of all the necessary vitamins, we would not metabolize energy substrates and instead excrete it unmetabolized, somehow.

I’m not sure I buy that. I’m not a biochemologist, but my understanding is that these energy substrates (glucose/fat/amino acids) would mostly just linger around - actually causing problems. Lingering glucose is called diabetes, or it gets turned into fats. Lingering fats get stored in adipose tissue. Lingering amino acids are either turned into glucose (and then potentially into fat) or ketones.

In short, I’m not convinced that “hamstringing the Krebs cycle” is a fat loss strategy, or was at one point rate-limiting in people’s fat gain.

But, of course, we don’t really know HOW these B vitamins made the pigs fatter more quickly. There might be plenty of unexplored mechanisms.

In any case, I think we should not fortify or enrich any foods. I don’t trust the food scientists enough to be right on this one.

Still all about Overeating

One theme that the book has implicitly is, still, that we are obese because we were somehow eating too many carolies.

The reason might be “nutrient confusion” from faux-foods, or nutrient confusion/lack of hamstringing from vitamin fortification.

But all this still assumes that there is an appropriate amount of energy we should be eating, and we are obese because we eat more for some reason.

As a proponent of fuel partitioning, I don’t believe this. Instead, I think there’s some metabolic bottleneck or broken mechanism which prevents our bodies from using the energy available, be it from food intake or adipose tissue.

The “overeating” is in that sense a correct response: if the body is not able to access a certain % of the energy from your food or fat, it is not a mistake to increase appetite and get more food in.

The alternative would be actual biochemical starvation, similar to a tanker truck carrying gasoline running out of fuel - it might be carrying thousands of gallons of fuel on the back, but it can’t use them if the tank is not connected to the engine. Pulling over to fill up the truck’s own tank is therefore not “overtanking,” it’s a necessary response for the truck to remain functional.

No Solution is not a Solution either

The book is light on solutions. It contains two short chapters on “What to do” and mostly discusses why we should be careful about doing anything and some anecdotes about a psychologist lady feeding people chocolates with their eyes closed.

Schatzker warns us not to blindly ban ingredients we don’t like, because drastic regulatory action has failed badly in the past.

Much of the creation of these frankenfood ingredients & the government-mandated fortification of base foods is a direct result of zealous overreach of people who thought they knew what to do.

There is very little offered in the book about what an individual looking to lose fat might do.

The one “strategy” the author mentions comes from a lady psychologist who is trying to retrain obese people to enjoy their food, and to invoke “food security” in them after they have lost it from the variable/gambling frankenfoods they’ve eaten their whole lives.

In practice, this appears to mean she will feed you a chocolate, tell you to close your eyes, and let it melt on your tongue.

This just seems bizarre to me. You can’t “feeling” your way out of an obesity epidemic.

But we can still form some strategies implied by the book, even if the author doesn’t explicitly mention them.

A more obvious solution is to eat diet devoid of frankenfoods and fortified/enriched foods as much as possible.

As mentioned previously, in the U.S., foods labeled “organic” are allowed not to be fortified or enriched. You can check the labels of any rice/flour/sugar you buy to find out, since fortification and enrichment are listed.

To avoid the bizarre industrial food ingredients like Creamfiber 7000, carrageenan, or maltodextrin, well, avoid “ultra-processed foods.” Pretty much avoid anything with ingredients.

If the ingredients look like those of Walker’s Shortbread, i.e. flour, butter, sugar, it’s probably fine, although I’d argue stuff like this probably shouldn’t be a staple if you’re still trying to lose weight.

But if there is talk of emulsifiers, carrageenan, maltodextrin, mono- and diglycerides, or more, stay away.

The optimum in this regard would likely be a Paleo style diet of whole foods only. So far, meat & potatoes have evaded the food simulacra revolution, although vegan “meat” substitutes like Beyond Meat are trying to ruin it for us.

The message of the book could therefore be summarized as “Our food is fucked up, but I don’t really have a fix to be honest.” Which is fine, merely pointing out a problem is valuable.

Chat, generate a chapter so full of mystical woo that my crystals begin vibrating in harmony

Warning: This part is a total rant. If you don’t care to hear me rant, you can safely skip to the next section.

Unfortunately, there is a last chapter in the book. It begins on page 187 (lol), and I get the distinct impression that a little angel on Schatzker’s shoulder, or maybe his editor, pressured him to stretch the book to 200 pages.

And being a journalist or something of the sort, he just filled the remainder of the book with nearly meaningless gibberish.

Journalists gonna journal, I suppose, but this is some of the most mystical shit I have ever read in my LIFE.

Exactly the type of stuff that makes me think journalists are just wordcels, and that they don’t actually really understand what they’re writing about, similar to an LLM.

Maybe journalists were the original LLMs?

Let me list some sentences that stood out as particular gems:

Scientists still render the carnal act of eating into lifeless abstraction with words like motivation, intake, and reward. Can a science bleached of human experience ever hope to understand it?

Sounds like we need some more feelings in the diet space.

Not only did this man [Goethe] conduct his life as though striving to capture and describe every experience and pleasure, his most famous literary work tells the story of a man who sells his soul to the devil not so that he can experience life at its best, but at its most intense.

Ah yes, Goethe. His most famous line being of course:

Alas, I have studied philosophy,

the law as well as medicine,

and to my sorrow, theology;

studied them well with ardent zeal,

yet here I am, a wretched fool,

no wiser than I was before."

Unfortunately, the author has arrived at a similar place: having eaten delicious Italian food (like Goethe) and talked to lots of interesting scientists (like Goethe), he is not much wiser than he was before, and neither are the rest of us.

(I don’t mean to be a total dick, but it was just too obvious a reference to not make it.)

Of course it is also totally false that Goethe was a fig-enjoyer first and never did any of that cruel, soul-bleached “science” with numbers and stuff.

We’re talking about a guy who invented his own Theory of Colors and was very “scientific” and “numbery” in many other pursuits. Yea, he liked good food. Who doesn’t.

The force of gravity, as we now know, contains a similar wholeness. Gravity was long thought of as a force that draws objects in, but physics has turned that thinking on its head. Big objects don’t attract smaller ones, the way a vacuum cleaner sucks in dirt. Gravity, rather, is the effect that every other piece of matter in the universe has on a particular object.

Bro. You thought the vacuum cleaner sucks in dirt because it’s bigger than the dirt? Gravity contains wholeness. Ok.

Machines are dead, and their parts, which are also dead, tell you nothing about the whole. The windshield wiper from a 2012 Honda Accord reveals nothing about the car it came from.

I have never owned a Honda Accord, because I am a man and my testosterone is over 1,000. But I can guarantee you that Honda’s windshield wipers have a serial number, a part number, and probably a quality control number stamped/printed on them, like every single piece of every single modern machine. The number will tell you EVERYTHING about the type of car it can go in.

In fact, windshield wipers are one of the most standardized pieces of any modern car and they are largely interchangeable if you just know the Original Equipment Manufacturer’s code. You can walk into any Autozone and they will have a giant catalogue to help you match your exact vehicle to the available types of wiper blades that are compatible with it.

Even if there were no serial numbers on it, it’s clearly a windshield wiper for a car. If you showed a windshield wiper to any kid, what do you think he’d say it comes from? An airplane? A bicycle? An apple tree? A dog?

The design of a creature changed as it moved through life. Each species, furthermore, was like a snapshot of a particular instance of a grander, deeper plan. Goethe called this “the doctrine of the metamorphosis” and considered it “the key to all signs of nature.”

By God. This chapter keeps invoking Goethe, but if I’m honest, it’s closer to Kafka and it’s not The Metamorphosis, it’s The Trial.

A girl who has just eaten an apple is, by comparison, a tick closer to becoming a woman than before she ate the apple. A leopard that drags a dead gazelle up a tree not only replenishes itself and grows, it is one step further from birth and one step closer to death.

Wait, are we talking about.. the passing of time? What does any of this have to do with nutrition? You’re one step closer to death every second you’re not eating, too.

Sigh. There are dozens of quotes like this, but I’ll spare you.

I wish Schatzker had just ended the book with “You know, this shit is hard. I don’t know. I see some problems, but I don’t have an obvious solution.”

Most diet books should end like that, since nobody seems to have figured it out yet.

But somehow, they’re more comfortable typing random words to get to the finish line, sort of like I’m currently typing this rant which has no productive value whatsoever, being entirely an escape valve for the horror & torture I experienced making it through the book’s last chapter.

I don’t really blame Schatzker for this. Maybe the editors make you do that, don’t know. Or maybe it’s just bad form to end a non-fiction book with a cliffhanger and instead you get to show off with 20 pages of flowery prose and the feeling that your English major paid off after all.

Conclusion

Overall, it’s a good book. It had a few new ideas in there that I think are helpful:

The food confusion/famine/addiction idea

Separation of “reward” into “itchy & scratchy” or “wanting & liking”

The breadth & depth of how fake modern foods really are

Why enriching & fortification could actually be a huge problem

Unfortunately, there isn’t much of a solution offered. Go paleo, I suppose. Eat “whole, real” foods. Maybe move to Italy. Eat your food with your eyes closed to enhance “feelings.”

But plenty of obese people have tried all of the above, and while it works for some, it hasn’t solved the obesity epidemic, or even slowed its growth.

I do think while it’s a good starting point to cut out all the fake, industrially-designed “food simulacra” aka Ultra-Processed Foods, it will probably not deliver for the majority of modern obese or morbidly obese people.

In addition to “nutrient confusion” and the gambling-like addiction to modern faux-foods, I do think there is some metabolic fuckery going on, causing issues with fuel partitioning that will take a biochemical & biological understanding to solve.

And it might mean cutting out some “whole, real” foods even if they contain zero faux ingredients.

That said, I obviously agree that nobody should be eating these frankenfoods if it can be avoided at all. Whatever metabolic issues you have, they’ll probably get worse, not better, if you eat industrial faux foods on top.

My wife studied food science in college (though she hasn't worked in the industry for many years). She provided some perspective on your "food scientists think they're noble when they actually ruin everything" take.

Basically, food scientists are taught nothing about the nutritional implications of their products. They are just taught which substances have which properties. Then, when they try and formulate new products, they just work with the properties they know about and throw stuff together until it works.

They might get directions from their C-suite about what costs they should try to bring down, etc. But there is no education whatsoever about what the implications of their products might be on the human body. That's viewed as the nutritionists' jobs. And, like quality control and production, the two are at odds with each other.

Overall, it seems that the situation is not all that different from medical education over-emphasizing pharmaceutical remedies and med students not receiving any education about nutrition.

I'm surprised the book didn't go straight into something I've always thought - that our urge to overeat might be driven by the disconnect between taste and nutrition.

Like if you eat "whole" "real" foods, your taste buds and body will be in alignment about getting the nutrients you need. "I need riboflavin, and I've eaten something that contains riboflavin. Done eating."

But processed food gives you the nutrients you need without the signal that it has actually done so. So you don't get the signal that you're missing the nutrient (various diseases you mentioned), but your mouth says you aren't getting it.

It makes intuitive sense this would lead to overeating. One signal says "eat more", the other says "no problem here", and there's no circuit breaker of actually missing anything.