A Metabolically Shaped Hole

..that a congruent theory of obesity has to fit into

After 20 years of thinking about obesity and experimenting with various diets and other methods of reversing my own (formerly morbid) obesity, I have formed some pretty strong opinions.

Most of the time when I encounter a new “theory of obesity” I can quickly dismiss it, because it often doesn’t fulfill some criteria that I believe are necessary to explain the modern obesity epidemic.

In short, a valid theory of obesity has to explain all the existent facts, but it also cannot “explain too much.”

An example of “explaining too much” is the thrifty gene hypothesis, which basically claims that we are genetically wired to overeat and store fat because we used to starve as cavemen.

Cool story bro, but how come my grandpa was rail-thin despite living with a fully-stocked fridge his entire life?

How come people didn’t get morbidly obese despite being rich?

In fact, how come the rich are thinner than the poor these days?

What a Theory of Obesity has to explain

This is an incomplete list, but it’s still a relatively high bar, and most theories don’t come close to explaining all of these points:

Explain the Mysteries of Obesity (shocker: I believe PUFA explains them)

Match the timeline of the obesity epidemic: started before 1900, took a big jump in 1970, but even from 2000-2025 there’s been an immense increase in obesity

Explain various ancestral tribes whose dietary patterns & health levels we’ve studied in the modern age (Tsimane, Masai, Eskimos, Hadza, ..)

Explain various crazy internet diets that show great success in many people (keto, high-carb low-fat, carnivore, ..)

Has to actually show root-cause analysis & a change therein, not merely trivial tautologies like CICO

It really helps if there are convincing mechanistic studies to explain the pathway(s) by which this theory works

I realize this is a high bar, and that most theories aren’t up to snuff. But that’s because any valid Theory of Obesity must be at least slightly complicated. If it wasn’t, we would’ve found it by now, and would’ve solved obesity.

Rick Johnson’s Polyol Pathway Theory

This was all just an introduction explaining why one new (to me) theory of obesity struck a chord immediately.

Richard Johnson, MD went onto a few low-carb channels in 2022 to promote this hypothesis and his book, titled “Nature Wants us to be Fat.”

I totally missed it at the time, maybe because I’ve largely tuned out of the low-carb community. I believe they are mostly a circle-jerk and I think that naive low-carb/keto has proven insufficient to explain the obesity epidemic, as detailed in my post Keto has Clearly Failed for Obesity.

But recently I was posting something about salt and the effects it seemed to have, anecdotally, on my own rice consumption in experiments of eating plain rice with and without (salted) marinara sauce.

Somebody pointed me to this 3-piece video series of Johnson at Low-Carb Down Under. Each part is about 45 minutes, and I recommend you listen to them all.

Nature Wants us to be Fat 1

Nature Wants us to be Fat 2

Nature Wants us to be Fat 3

If you don’t want to listen to Johnson, or if you just want to get a summary before spending so much time on this theory, let me briefly explain it:

Fructose is bad. In excess (which really isn’t much as concentrated fructose is rare in nature) it is converted to fatty acids by the liver, and can lead to fatty liver disease or just regular fat gain

Therefore eating large amounts of sugar is bad (so far, this is just low-carb/Dr. Lustig dogma)

BUT the fructose you eat isn’t the only fructose in your body - there is a so-called polyol pathway, which will turn glucose into fructose endogenously if activated

The evolutionary explanation for this pathway is likely the ability of animals to get into torpor and accumulate fat reserves for winter or the dry season. Hey, this sounds suspiciously like Brad Marshall’s Torpor theory!

Switches to activate this polyol pathway include: high salt intake (or general dehydration, think camels storing water reserves in their fatty humps), high glutamate (umami flavor) intake, high-glycemic (i.e. rapidly digesting) carbs in general.

When activated, this polyol pathway produces uric acid, which can turn NAD+ into NADH (I think), which I won’t pretend to understand but contains the same words that Brad from Fire in a Bottle & Peter from Hyperlipid talk about. In short, my understanding is that this turns the Fuel Partitioning Switch from “burn all the fuel for energy” to “store some of the fuel as body fat,” which decreases the energy available from food intake and therefore causes extra hunger.

An analogy: say you make $1000/mo from your job and you spend $700/mo on rent, food, and so on. This would allow you to save $300/mo for retirement. But say that you set up a retirement switch that automatically routed $500 off your paycheck into your retirement account. All of a sudden, you wouldn’t have enough money left over to pay your bills! You’d have to get a second job to cover the difference, aka “overeat.”

I.e. it’s not overeating that caused your fat storage, a chemical switch diverted fuel substrate from energy production to storage, decreasing available energy - your increased appetite is totally “correct” in that sense.

In nature, this “become fat for torpor” mechanic is only switched on to fatten up for the winter/dry season, but in our modern food environment, we are accidentally activating this switch all the time.

Brad & Peter both think that linoleic acid is the main root cause of this, but Johnson’s polyol pathway theory explains how other things like fructose, excess salt, and even more could also lead to activation of this pathway.

Anecdotal evidence just in myself

One reason why this theory immediately resonated with me is that it would explain several “weird” phenomena I experienced in recent months in my own dietary experiments.

As a reminder, as a scientist you should say “huh, weird!” all the time when you find something that you can’t explain, not “it’s probably just the wind.”

Example 1: ad-lib food intake of rice with and without marinara sauce

If you don’t recall, I started experimenting with high-carb, moderate-protein, very-low-fat diets last year after 9 years of strict keto.

My first such experiment was ex_rice, in which I ate ad-lib white rice with ad-lib fat-free marinara sauce from Whole Foods. This marinara sauce is of course mostly tomato sauce, but also contains delicious Italian herbs & spices and salt (sodium).

During this experiment, I ended up eating almost exactly the same amount of carolies that I measured last time on my ex150 heavy-cream diet: 3,300kcal on average. Given how these are almost opposite diets, one being 90% fat and the other about 90% carbs from rice, this was quite surprising.

I also didn’t lose any weight at all.

Then I read some more about Walter Kempner, the inventor of The Rice Diet. He actually believed that salt was the bad guy, and his diet was often not referred to as “rice diet” but “low-sodium diet” at the time.

Hence I recently tried a pure, plain white rice diet with no added sodium and no sauce at all: ex_plainrice.

And, somewhat shockingly, I lost 5.5lbs. Now it’s quite likely that not all of these were fat, but just reduced water retention from the low sodium. Still, it brought me to my lowest weight in a year.

This experiment was also ad-lib white rice, and I only ate about 2,350kcal/day! A spontaneous reduction in heat unit intake by nearly 1/3?! How weird!

I had no way of explaining this. After all, both diets were quasi fat-free, and therefore equally free of PUFA. Additionally, the marinara sauce, if anything, would have contained a small amount of carolies - in terms of pure energy satiety, I should’ve eaten LESS rice to make up for that?

Huh, weird.

Clearly, it seemed, the sauce was making me eat more. “Of course,” some said, “it was more delicious so you ate more.” But I am skeptical of the whole “delicious food makes us overeat” theory and didn’t fully buy it.

Johnson actually tested the “good taste” theory in mice: he engineered mice that could not taste sweetened beverages at all. The mice still preferred fructose-sweetened beverages over plain water, and became fat & metabolically unhealthy.

There appears to be a metabolic effect of fructose here that is independent of actual flavor or “good tasting food.”

Since tomato sauce is concentrated umami, and this one was dosed with sodium, it would’ve activated the polyol pathway, and my body would’ve converted some of the glucose from rice into fructose.

Example 2: ad-lib food intake on a near-zero-fat diet

Between ex_rice and ex_plainrice I tried another variant, a high-carb, medium-protein, low-fat diet. It wasn’t quite as close to zero in fat, and the protein was higher because I ate lean bison every day.

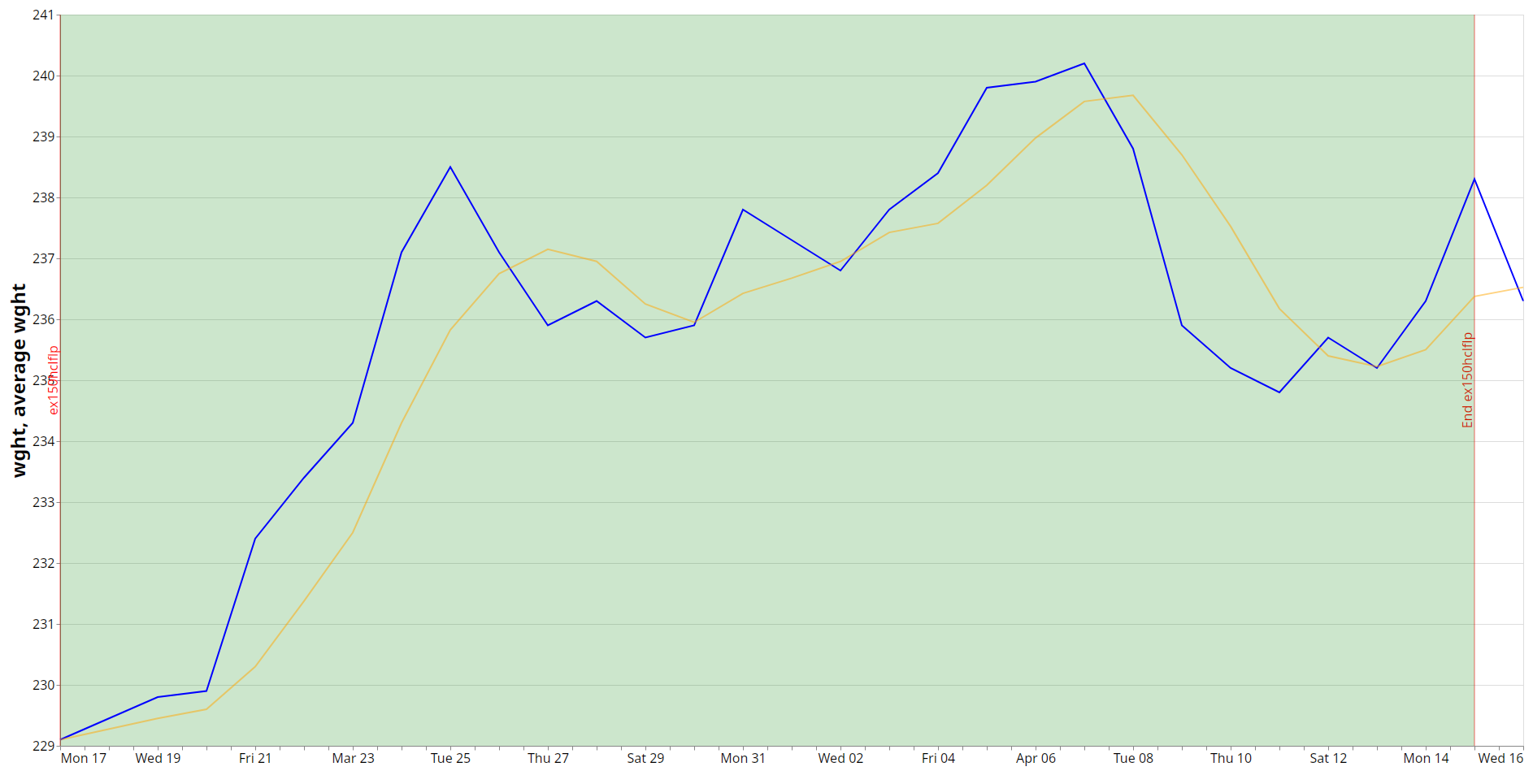

This was ex150hclflp. Here’s my weight curve from that month:

See that huge spike of gained weight the first week or so? That was when I mixed glucose (rice w/ sauce) and fructose (fruit/honey). My appetite became insane. I would eat my entire 3,300kcal ration of rice + marinara sauce, and eat several huge bowls of cut up fruit & drizzled with honey ON TOP of that. Clearly, the sugar was making me ravenous. Something felt very wrong, too, I felt bad almost the entire time.

After about a week or so, I had gained over 5lbs that would later (by DEXA) turn out to be actual fat, and I stopped doing the fruit & honey, turning this into mostly a rice, sauce, and bison diet.

The weight gain stopped and my appetite normalized.

Curious. Fruit & honey are both fat-free, and therefore PUFA free. It couldn’t be PUFA. Sure, rice + bison contained more protein than ex_rice would’ve, but then why did the ravenous appetite & weight gain stop after I ceased eating the sugar?

Clearly, mixing starch & sugar messed me up in some way.

Huh, weird.

This is of course easily explained by the polyol pathway theory: if fructose has the same torpor-inducing effect as linoleic acid, and shunts fuel substrate from energy production into fat storage, my fat stores would grow and my appetite would increase. A 50% increase in appetite is very dramatic, and so is gaining 5lbs of actual fat in just a week or so.

But I was pretty much maxing out the polyol pathway anyway: 3,300kcal of glucose (rice), with maximum umami (concentrated tomato sauce) and high sodium (also from the sauce) with ad-lib sugar on top (fruit + honey)..

The only thing I wasn’t doing was chugging corn oil with it.

This explains gaps in low-carb

Low-carb has mostly been superseded by keto and carnivore these days, but the ideas are pretty similar.

I think that these salt/umami/polyol pathway mechanisms can explain a lot of failure cases that naive low-carb (“don’t eat many carbs”) and even the more fructose-based low-carb advocated by e.g. Lustig can’t explain.

After all, it seems that you don’t have to actually eat much fructose - you can convert glucose inside your body into fructose, and of course your body makes its own glucose via gluconeogenesis all the time.

For certain people, therefore, high salt consumption, umami/glutamate consumptions, or something similar could be enough to cause all the ills of excess sugar intake - even on a nominally low-carb, sugar-free diet.

But some people do fine on high-salt?! Sure, and some do fine on high-fructose or high-carb. As usual, there’s probably a significant amount of variation from genetics, epigenetics, or who knows what.

Yet given how low-carb clearly doesn’t work for more than about 30% of obese people, maybe we should look at these other mechanisms. If someone’s doing great eating low-carb with high salt, fine.

But if someone’s failing to lose weight eating low-carb and high salt, why not give low-salt a try? If someone isn’t losing the weight as expected while eating enormous amounts of tomato sauce (like I did on ex_rice), why not try cutting out all tomato products for a month?

These all feed directly into the proposed mechanisms every low-carber already believes in. It would be silly to pretend they can’t be messing things up when eating actual sugar can.

Addenda from Jaromir Janda

I mentioned Jaromir recently when he explained some studies on vinegar, and how the acetic acid in it can have protective effects.

When I posted about Johnson and the polyol pathway, Jaromir linked to some posts he’d previously written on the topic, shortly after Johnson came out with these ideas.

I recommend you go and read both these posts by Jaromir, as they make the connection between Johnson’s polyol pathway hypothesis and linoleic acid:

What does sugar, fruits and juices do with metabolism? And what about beer or wine?

How to make fructose in the liver, but you better not do it!

Interestingly, Johnson doesn’t seem to make any mention of PUFAs or linoleic acid or seed oils. Like most traditional low-carbers, the distinction between different fats seems to completely elude him.

And that despite talking about torpor, and how fructose can induce this in humans. Of course Brad Marshall talks about our modern obesity epidemic being reminiscent of torpor, induced by the consumption of high-linoleic acid foods.

Jaromir’s posts tie these 2 ideas together very nicely. It turns out that these 2 systems influence each other. For example, not just the production but also the excretion of uric acid via the kidneys is important.

And what, according to Jaromir, can block the excretion of uric acid? High free fatty acids in the blood, a common side effect of excess linoleic acid consumption.

In fact, Jaromir suspects that most of the polyol pathway damage in modernity is dependent on a high-PUFA context. After all, we don’t seem to see as much damage in ancestrally-living hunter gatherers that seasonally eat high amounts of fruit or honey, or salt.

Could the endogenous production & negative effects of fructose, as explained by the polyol pathway, be another downstream victim of excess PUFA?

Traditional Diet Advice - in the proper context

When listening to Johnson’s presentation, I realized how this nicely framed a lot of “traditional” diet advice in a certain context.

Eat fruit, don’t eat candy/drink soda

Eat lots of fiber (to slow digestion of fructose)

Eat less salt/drink more water (to reduce salinity in the blood)

All of this advice is sort of made fun of in the keto/carnivore community. But it might be good advice IF you’re in a high-glucose, high-PUFA context, like most of us have been for the last 100 years. And especially coming from a healthier agrarian starch-based but low-PUFA context, like most people ate since the agricultural revolution.

If you’re gonna be mostly starch-based, and you’re already PUFA’d, all of that advice is probably sound.

Now you can totally avoid glucose metabolism to a degree by going keto/carnivore, but you can’t shut off gluconeogenesis completely.

And you can avoid eating fructose, but are you avoiding the polyol pathway, or are you slamming salt/umami/glutamate?

I’d say that if you’re not quite metabolically healthy despite avoiding carbs or PUFAs, and you’re habitually consuming high amounts of salt, umami type foods, or plain fructose or sugar, I’d give this theory a try.

Personally, I’m guilty: I’m a total tomato sauce addict. A friend jokingly calls ex150 “the sauce diet” because I put almost more sauce than meat/vegetables into each meal.

To test out this new hypothesis, I’ll be doing ex150nosauce next: just 150g of beef and a little bit of green vegetables, with ad-lib cream as before.

Knowing that I can deal with plain rice without sauce for a month, this should be a piece of cake in comparison.

Maybe it was the high-sodium, high-umami marinara sauce the whole time?

Not sure what to think about this one. The Japanese diet is high in starch, salt, umami (the word is even Japanese) and despite my wife’s protestations (Japanese) has a fair bit of sugar in it, but you don’t see many fat people in there, particularly in more rural areas.

I laughed out loud at "heat unit intake"!